1. Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center School of Medicine, New Orleans, Louisiana.

2. Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, Louisiana.

Keywords: emergency medicine; social determinants of health; screening; community resources

Social determinants of health (SDOH) screening in emergency departments (ED) is a promising method to capture and address individualized social needs of a broad patient population, ideally lowering emergency department readmissions while reducing health disparities. With new Joint Commission guidelines requiring social determinants to be addressed and integration of SDOH-related Z-codes into ICD-10 coding, the time is now to implement robust screening and referral programs. This narrative literature review strives to identify best practices prior to the implementation of social determinants screening in the ED of University Medical Center, New Orleans. We investigate current screening tools and their integration with electronic health records, discuss survey formats, detail referral processes, and resource navigation post screening, and describe care connection models from screening to referral. Key conclusions include the identification of the Protocol for Responding to & Assessing Patients' Assets, Risks & Experiences (PRAPARE) as the ideal screening tool, and that electronic screening tools led to higher levels of social needs reporting compared to paper counterparts. Similar success of written resource referrals and referrals given by a navigator in reducing social risk factors was also identified, highlighting the importance of high-quality, written resource referrals. Lastly, challenges to formation of a successful, integrated screening and referral pathway such as loss to follow-up, even in a transition care coordination model that assists patients throughout levels and types of care, are identified.

Emergency room services play a critical role in public health. According to Ordonez et al. (1), patients with food insecurity, lower education levels, limited access to primary care services, members of racial and ethnic minority groups, and Spanish-speaking patients with limited English proficiency were all correlated with higher ED utilization. Such groups experience systemic barriers in access to care and emergency care transitions. This may lead to greater health disparities, which tend to be strongly associated with increased adverse SDOH (2). SDOH strongly impacts one's quality of life and life expectancy. According to Alley et al. (3), measurable health outcomes such as mortality and morbidity receive approximately 55% contribution from social, economic, and environmental factors.

This literature review is being conducted as a review of current practices prior to the introduction of a revamped SDOH screening and referral system in the ED of University Medical Center, New Orleans (UMC). New Orleans and its people are uniquely positioned to reap the benefits of this intervention for many reasons. According to the New Orleans Community Health Improvement Plan (6), only 65% of New Orleanians have a primary care provider, yet chronic conditions are commonplace, with ⅓ of residents suffering from hypertension or hypercholesterolemia and ⅔ of residents considered obese. New Orleans is the second most food insecure city nationally and nearly ¼ of its residents live in poverty, with the city's average household income being $41,604, over $20,000 under the national average (6). Using the ED to connect New Orleanians to necessary resources such as food banks, housing resources, mental health care, preventative healthcare services, and more will hopefully address some of these issues while lowering ED readmission rates by tackling root causes of admission.

Additionally, with the introduction of a new National Patient Safety Goal by The Joint Commission targeting health equity, hospitals, and other healthcare institutions are more directly incentivized to address social determinants than ever (7). Effective July 1st, 2023, this goal requires institutions to assess patients' health-related social needs, analyze quality and safety data to identify specific disparities, and develop action plans to improve health equity (7).

Henrikson et al. (9) reviewed literature published from 2000 and 2018 to yield 21 unique screening tools for social risk factors in a clinical setting and assessed them on their psychometric and pragmatic characteristics. Tools that are deemed psychometrically strong are able to "accurately and precisely identify social risk domains, characterize their associations with relevant outcomes, and measure changes in risk over time and in response to interventions" (8). Tools that are pragmatically strong were deemed as having favorable pragmatic properties such as ease of administration, low cost, and shorter lengths (9). The top 3 scoring tools for psychometric testing were: Urban Life Stressors Scale, Protocol for Responding to & Assessing Patients' Assets, Risks & Experiences (PRAPARE), and Social Needs Checklist (Henrikson et al., 2019). According to Henrikson et al. (2019), the top 3 scoring screening tools for pragmatic testing were: Survey of Well-Being of Young Children, Safe Environment for Every Kid, and WeCare.

In a systematic literature review conducted by Chen et al. (5), 4 main SDOH screening tools were focused on. These were the PRAPARE tool, the Accountable Health Communities (AHC) Screening Tool, the Health Leads Screening Tool, and the HealthBegins Upstream Risks Screening Tool.

According to the literature review, all 4 of the above screening tools cover the 5 key domains outlined by Healthy People 2020, a 10-year program launched by the United States Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) with an objective of improving health through goals like reducing health disparities and reducing preventable disease. These key domains were economic stability, neighborhood and built environment, health and health care, education, and social and community context (5). The review noted that PRAPARE covered the most measures in every domain except health and health care. In this domain, PRAPARE focused on insurance status while the other 3 screening tools focused on needs for assistance, physical activity, diet, and mental health status (5).

Other studies (10) have shown success with utilization of the SDOH screening tool native to EPIC. Benefits included question alignment with other institutional EPIC users, easy access to EPIC population health tools, and quick accessibility of survey responses to team members.

Utilization of surveys native to mobile apps was also reported (11), including use of HelpSteps, a self-administered screening tools which allows users to choose from 22 different domains of social determinants with accompanying referral options, and simply select their most important, and secondary need domains. This survey was combined with the widely adopted AHC Health-Related screening tool (Table 1).

Table 1. Top Ranked Screening Programs

| Program | Description |

|---|---|

| Urban life stressors | A 21-item screening survey for adult patients designed for a primary care setting. It assesses economic security, social and community context, and neighborhood and physical environment. It was determined as one of the top 3 screening surveys for psychometric testing by Henrikson et al. (2019). |

| PRAPARE | A 36-item screening survey for adult patients in a primary or specialty care setting. It assesses economic security, education level, social and community context, health and clinical care access, and neighborhood and physical environment. It was determined as one of the top 3 screening surveys for psychometric testing by Henrikson et al. (2019). |

| Social Needs Checklist | A 12-item screening survey for adult patients in a primary care setting. It assesses economic security, social & community context, health and clinical care, and neighborhood & physical environment. It was determined as one of the top 3 screening surveys for psychometric testing by Henrikson et al. (2019). |

| Survey of Well-being of Young Children | A 10-item screening survey for adult and pediatric patients in primary care and pediatric settings. It assesses education level, neighborhood & physical environment, and food insecurity. It was determined as one of the top 3 pragmatically strong screening surveys by Henrikson et al. (2019). |

| Safe Environment for Every Kid | A 20-item screening survey for pediatric patients in a primary care setting. It assesses social & community context, health and clinical care, and neighborhood & physical environment, and food insecurity. It was determined as one of the top 3 pragmatically strong screening surveys by Henrikson et al. (2019). |

| WeCare | A 10-item screening survey for pediatric patients in a primary care setting. It assesses economic security, education level, neighborhood & physical environment, and food insecurity. It was determined as one of the top 3 pragmatically strong screening surveys by Henrikson et al. (2019). |

| Health Leads Screening Tool | A 7-item screening survey for all patients in a primary care setting. It assesses economic security, education level, social and community context, food insecurity, and neighborhood and physical environment. |

| Accountable Health Communities (AHC) | A 26-item screening survey designed for Medicare/Medicaid patients in a primary care setting. It assesses economic security, social and community context, food insecurity, and neighborhood and physical environment. |

| HealthBegins Upstream Risks | A 28-item screening survey for all patients in a primary care setting. It assesses economic security, education level, social and community context, food insecurity, and neighborhood and physical environment. |

A study conducted by Gottlieb et al. (12), used both electronic and face-to-face screening surveys in a pediatric ED to assess the difference between the two formats.

The study identified significant differences between the responses from the computer-based surveys and face-to-face interviews, with people being more likely to report social needs items in the computer-based surveys (12). Respondents reported higher levels of stress related to interpersonal violence (p=0.03) in their homes through computer-based surveys (12). The survey also included higher levels of reported substance use in the home (p=0.05) through computer-based surveys (12). This study is important in demonstrating the significance of the methods of data collection as these methods can affect accuracy and disclosure rates of the patients. A key takeaway from the study is the advantages of using computer-based screening tools, which may be more advantageous as they eliminate feelings of shame or judgment towards patients that may be associated with answering these questions posed directly by a medical provider.

Electronic screening allows surveys to be implemented in a universal fashion, with all patients screened to eliminate non-response bias, as less staffing and administrative resources are needed for administration. This aids in the prevention of certain patients not being screened due to external appearance or demographics. One study (12) found a significant difference in financial insecurity between social screening respondents and non-respondents.

After SDOH screening through an EHR-integrated tool, results should be used to connect patients to appropriate services. A study conducted by Gottlieb et al. (14) explored the effectiveness of in-person social services navigation assistance in comparison to sharing standardized written information regarding available social resources. The purpose of this study was to investigate methods to make long-term care more feasible and effective in a pediatric urgent care clinic by addressing social risk factors. The study randomized patients to receive either written resources or written resources plus in-person assistance. The written resources were prewritten informational handouts that listed local resources from relevant government, hospital, and community social service organizations. The in-person assistance consisted of navigators who also provided other forms of assistance to caregivers such as help with scheduling appointments and completing forms.

The study found that there were no significant differences between the two groups, but that both groups had significant decreases in reported social risk factors (examples included food insecurity, housing insecurity, and transportation access) as well as improved child and caregiver health. According to Gottleib et al. (14), the results of the study were unexpected as a previous study conducted by the same authors had shown that in-person navigation of resources was significantly more effective. Gottleib et al. (14), discussed that the potential reason for the difference in results could be attributed to the improved quality of information given in the resource sheets. In this study, the navigators incorporated 2 techniques that were recommended by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. These techniques were to include specific contact names at the organizations given and highlight the resources that are most relevant to the social risks identified (14). High-quality written resources may be a sufficient social risk intervention in pediatric populations.

Applications that automatically generate referrals based on screening responses have also been used, and can be combined with an optional social work consultation. A study (11) with this approach reported that 14% of the study population reached out to a social support organization.

Community partners, defined as pre-existing organizations that may address specific social determinants of health such as food banks, shelters for the unhoused, or domestic violence prevention programs in addition to programs that focus more broadly on coordinating social needs interventions, are an invaluable resource in executing resource referrals. The strategic utility of these organizations in ensuring high follow-up rates and connection to care cannot be overlooked and strong relationships between healthcare providers and high-use community partners should be cultivated (15). A large academic medical center set up data sharing with an existing community resource directory organization, United Way of Salt Lake City's 2-1-1. Of the 129 patients with 1 or more stated needs, 73 (56.6%) asked for referral to 2-1-1 and 32 (43.8%) were reached by 2-1-1 within 1 week of emergency department discharge (14).

A study conducted by Hsieh (16), showed that resource navigators could link patients to primary care providers and other emergency providers. This would allow for continuity and advocacy for the patient's social concerns. For many high-risk patients, resource navigation may not be sufficient, and establishing ongoing care is a more effective way to intervene in the complex medical issues these patients may be facing.

Some papers have described their processes for addressing social needs from start to finish, from initial screening to connection to care or provision of social services.

A systematic review conducted by Yan et al. (17) explored current literature that investigated the process of integrating SDOH or social needs screenings into EHRs and subsequent care connections. They identified three main approaches to identifying and addressing social needs. The simplest approach involved healthcare providers identifying social needs and distributing community resources or referrals as they deemed appropriate. The second approach involved healthcare providers identifying social needs and then, using patient navigators to connect patients to external resources or social services. The third approach, the most complex, involved a transition care coordination model that assisted patients throughout levels and types of care at multiple facilities. Overall, Yan et al. (17) found that while many studies explored the process of integrating SDOH screenings, few studies actually reported health outcome measures. They noted that several studies did report positive impacts on healthcare costs and utilization measures, however, these studies were mixed in their ability to provide conclusive evidence.

This is congruent with a study conducted by Wallace et al. (18). In this study, the authors evaluated the reach and implementation of integrating SDOH screening and referral to resources in an ED. Between January 2019 to February 2020, ED registration staff screened patients for social needs. They used a 10-item, low-literacy, English-Spanish electronic questionnaire that generated automatic referrals. Wallace et al. (18) found that of the 4608 patients approached, 61% of patients completed the screening questionnaire. Of these patients, 47% indicated a need for one or more social services and 34% of those agreed to be followed up with a resource specialist (18). Only 20% of those who agreed to be followed up with were reached out to by outreach specialists for referrals. Only 7% of patients completed the process from screenings to referrals. This overall low completion rate should be considered when implementing referral processes. The article then explored the challenges that arose during this process such as patient stigmatization and staff reluctance. Detailed evaluation of the process determined that patients desired a better understanding of their needs and had felt concerns regarding privacy and being stigmatized from the screening staff. The screening staff expressed discomfort and that they were questioning the usefulness of screening for social needs.

Some authors have described utilizing automation to increase efficiency from screening to referral. An article by Rogers et al. (19) described a custom screening tool they built into Epic EHRs. The screening tool used was reflective of the AHC screening tool, mentioned in Section 1. Rogers et al. (19) customized the tool by integrating it with a Community Resource Network Management Software-as-a-Service (CRNM SaaS). The steps of the process began with the AHC screening tool. Then, these responses were recorded in the patient's EHR and transmitted from EHR to CRNM SaaS platform. The CRNM software reviews the screening results and automatically generates a customized community resource sheet (CRS) that can be given to the patient with their After Visit Summary (AVS). This tailored CRS includes community service providers (CSPs) in the patient's ZIP code or nearest ZIP code that could assist with each SDOH identified in the AHC tool. The strengths of this program were the reduced burden on healthcare staff. Additionally, providing patients with a customized CRS can help account for language or literacy barriers that may prevent the patient from using the information listed on the sheet.

Table 2. Integration of Literature Review Findings into Proposed Intervention

| Section of literature review | Incorporation into proposed intervention |

|---|---|

| Section 1: Discussion of Current Screening Tools | Similar to the successful screening tools, like PRAPARE, described by Chen et al. (5), our selected survey covers the 5 key domains outlined by Healthy People 2020. Because of its EPIC integration, it enjoys the benefits described by Peretz et al. (10) like access to population health tools and easy accessibility to care team members. |

| Section 2: Discussion on Formats of Surveys: Electronic versus face-to-face screening surveys | The screening survey is first offered in an electronic format that the patient can fill out alone. This follows recommendations from Gottlieb et al. (12), whose research showed patients were more likely to disclose social needs through electronic formats. |

| Section 3: Use of Referrals and Resource Navigation | The screening survey is paired with the tool FindHelp which can be used to curate a written list of community organizations and referrals that will be sent home with the patient based on the identified SDOH. This follows recommendations from Gottleib et al. (14) who demonstrated that patients given written resources or written resources plus in-person assistance had similar significant decreases in reported social risk factors and improved child and caregiver health. |

| Section 4: Putting it All Together: Use of Care Connection Models | When implementing our survey the recommendations of Rogers et al. (19) were used. Rogers et al. (19) described a custom screening tool they built into Epic EHRs and customized by integrating it with a community resource network tool that included resources in the patient's After Visit Summary. At our institution this was similar to the program FindHelp, mentioned above. This was designed to preemptively address common challenges, such as the burden on healthcare staff, that other institutions had faced when implementing screening tools. |

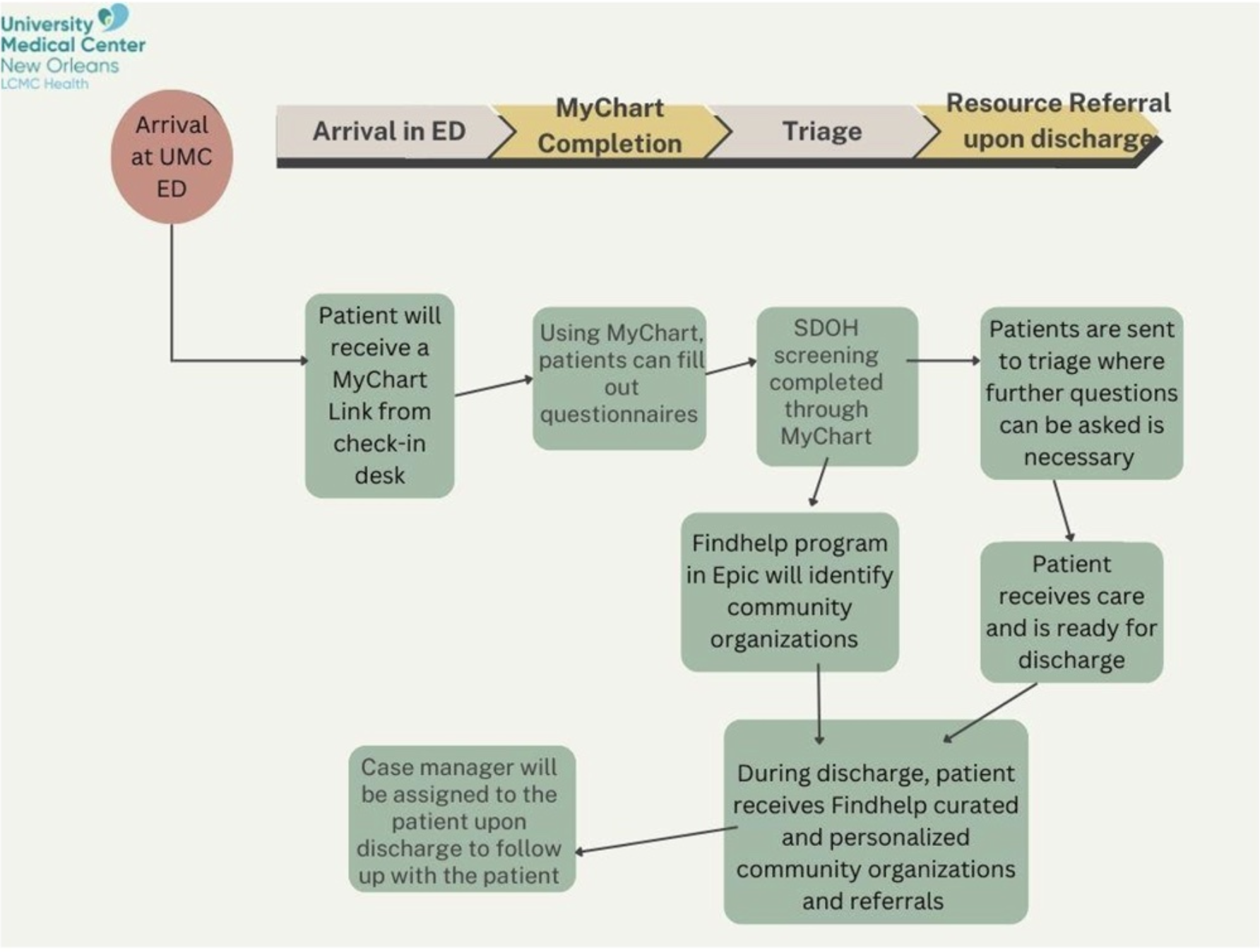

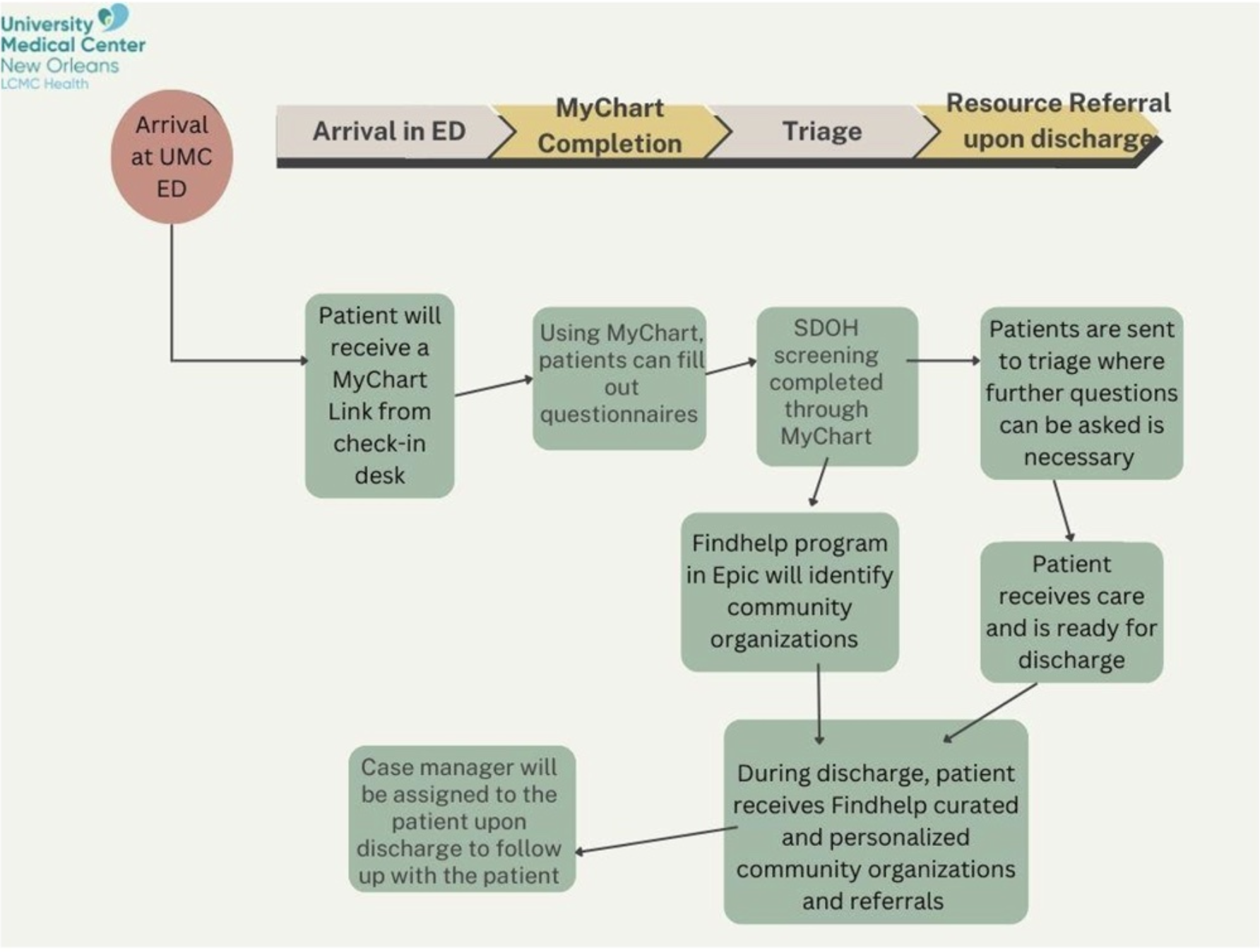

As described in Table 2 above, we recommend implementing a program similar to the one described by Rogers et al (19). Based on the demographics in New Orleans and the patient population at UMC, we propose utilizing a social determinants screening tool built into EPIC as well as the integration of a program called FindHelp into Epic. FindHelp uses a unique platform to connect people to local resources and programs. We have outlined a flow chart of our proposed intervention in Figure 1.

The recommended process will be as follows. When a patient arrives at the UMC ED, they will receive a link to MyChart. MyChart is a secure location that stores a patient's health information including medications, medical bills, test results, and appointments. Through MyChart, the patient will be able to complete a SDOH screening survey (Figure 2).

Figure 2. SDOH screening survey to be implemented.

The patient will then be sent to triage where the triage nurse will verify survey's completion or answer any questions to facilitate its completion. The survey tool will be added to the EPIC toolbar for easy accessibility to staff. If the survey is not completed pre-triage, or during triage, it can also be completed afterward while waiting for care. Once the patient has been treated and is ready to be discharged, a curated list of community organizations and referrals will be sent home with the patient based on the SDOH FindHelp identified from the survey. A case manager will also be assigned to the patient to follow up with them and provide any additional assistance.

Potential weaknesses of this program include its reliance on patients having a mobile device to access the internet. The MyChart link will be sent to a patient's phone either through text or email. If a patient does not have a phone, we hope to have ED iPads that can be used to fill out the screening surveys. Another weakness is that this program may be difficult for patients with low literacy levels, low proficiency in English, or disabilities. Providing iPads with accessibility features could help combat this issue but would require staff to be available to assist these patients.

SDOH screening is an important and growing objective in social Emergency Medicine. Beyond its importance in reducing hospital readmission rates by addressing root cause of disease or ED presentation, screening efforts address the new National Patient Safety Goal by The Joint Commission and have recently been integrated in ICD-10 coding.

Z codes are a separate set of ICD-10 codes that can be used to document patients' SDOH (22). They include a wide range of issues such as education & literacy, employment, housing status, access to food, access to safe drinking water, occupational hazards, and more (22). The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services' Office of Minority Health (23) released a report in June 2023 that maps out steps to effectively using Z codes. The steps they recommend are the following: (1) collect SDOH data, (2) document the SDOH data in the patient's record, (3) map SDOH data to Z codes, (4) use SDOH Z code data, (5) report SDOH Z code data findings. There are several benefits to collecting this information such as helping the hospital and healthcare staff identify the most commonly used Z codes. Identifying top Z codes can help focus referrals and resources in those specific areas and help to efficiently reduce SDOH.

There is also ample room for future research in this arena, such as an evaluation of follow-up rates with referral services to determine if the resources are being used and to what extent. Future research can also be done to explore SDOH screening implementation in settings other than critical/urgent care settings.

The role and efficacy of healthcare systems in implementing their own social needs interventions that do not require support from community organizations is another area the literature is lacking. Social determinants screening data can potentially be used to tailor interventions relevant to hospitals' unique patient populations. For example, a large proportion of patients indicating food insecurity during screening may indicate that a hospital-run food pantry would be beneficial. By implementing interventions without the reliance on partner organizations post-referral, healthcare entities may be better able to follow-up with patients and connect them to resources in a timely manner post-screening.

Following these recommendations for the SDOH screening process in the ED of UMC, robust collaboration, feedback, and training will be needed to ensure this new process is streamlined and effective for all stakeholders. After its complete rollout, data analysis and quality improvement initiatives will be necessary to ensure completion rates are as high as possible and that patients are being connected to needed resources in a timely and efficacious manner.